Inmigracion Topografia: The Incineration of Migrant Dreams

Prelude

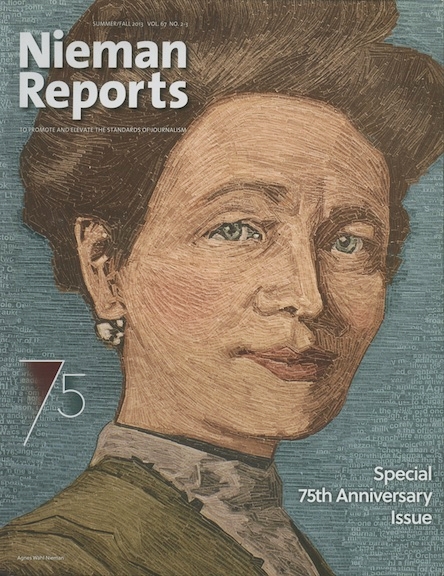

When I arrived at Harvard University to begin a fellowship at the Nieman Foundation in August 2009, I was ground down. I had spent twenty years photographing people at very close proximity in acts of war or violence in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Middle East for weekly news magazines. By the mid-2000s, I felt I’d become engaged in a hierarchical and increasingly proscribed form of journalism. I am grateful for the opportunities I had during that act of my career, but after twenty years, I wanted to step off the carousel and change my relationship with journalism and the media and my interaction with the communities that had been such generous hosts.

I felt constrained by the orthodoxy of the media and the practice of the craft as I had experienced it. A lot of contemporary journalism had begun to feel like a formulaic straightjacket, determined by political or cultural prejudice. With dramatically decreasing numbers of readers and shrinking budgets matters were sure to become increasingly severe. When I began my career my own libertywas critical, I always felt it was essential to integrity, honesty and fairness in journalism and the constraints I felt appeared to me to put that liberty, and integrity at risk. I knew I wanted to remain at large and engaged as a storyteller with the parts of the world I cared deeply about, but I wanted to change the process and the outcomes.

I had no idea what I would find at Harvard, and while I sought nothing specific, I was hoping to find something that would at least help me begin to shape what would come next.

I took three courses that changed everything: Constance Hale’s “Narrative Writing” course at the Nieman Foundation gave me the courage to experiment with the wonder of writing; Anne Mc Ghee’s “Life Drawing” class at the Graduate School of Design, courtesy of the Loeb Fellowship, helped me leave the violence behind and see without a camera; perhaps most important of all was Prof. John Stilgoe’s “Studies of the Built North American Environment.” Prof. Stilgoe helped me see beauty, significance, and nuance in what were hitherto the most unremarkable places. I saw magic in the unspectacular. He helped me re-embrace the possibilities of imagery and visual narratives and look for things I would never have looked for before.

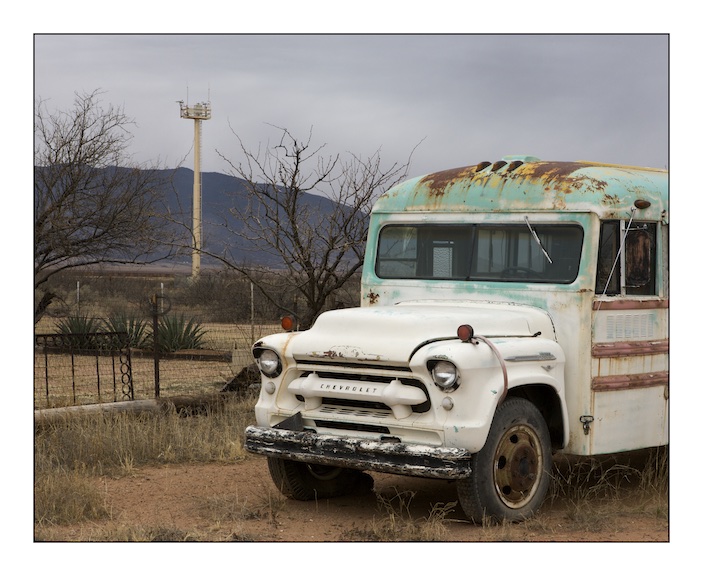

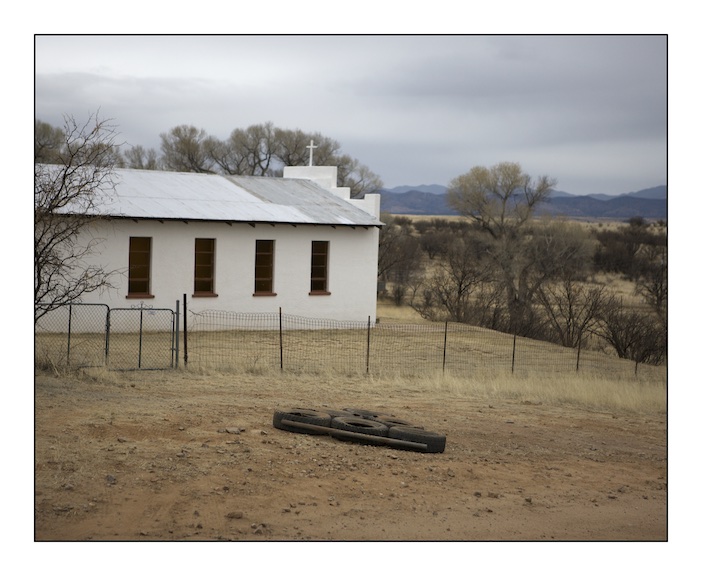

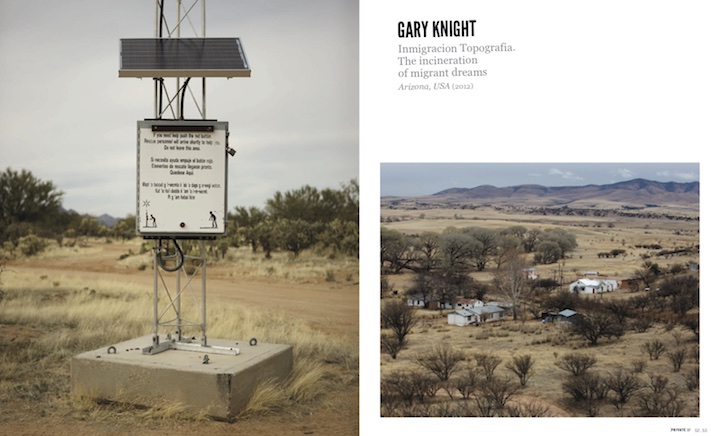

When I left Harvard, I picked up a camera for the first time in a year and went to Arizona to photograph a story on the issue of immigration, using the built environment—the landscape—as the sole character in the story. This would have been an unthinkable idea for me just a year earlier.

Introduction

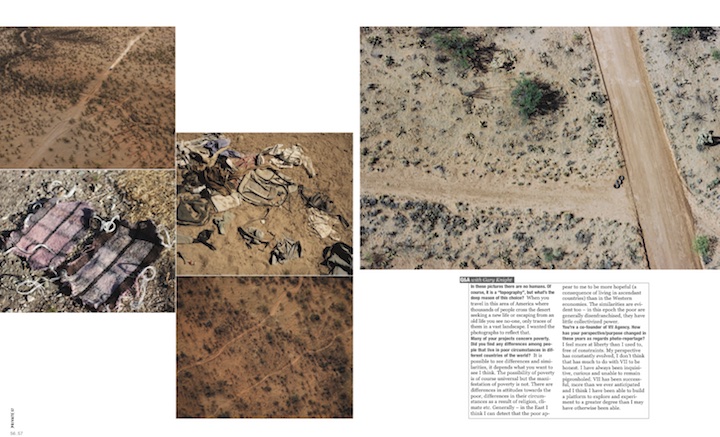

This is a story about migration, the illegal migration of thousands of men, women and children from Central and South America into the United States through one of the most hostile environments in the world. The project utilizes the photography of the topography and landscape of the Sonoran Desert, with the use of aerial, landscape and macro imagery.

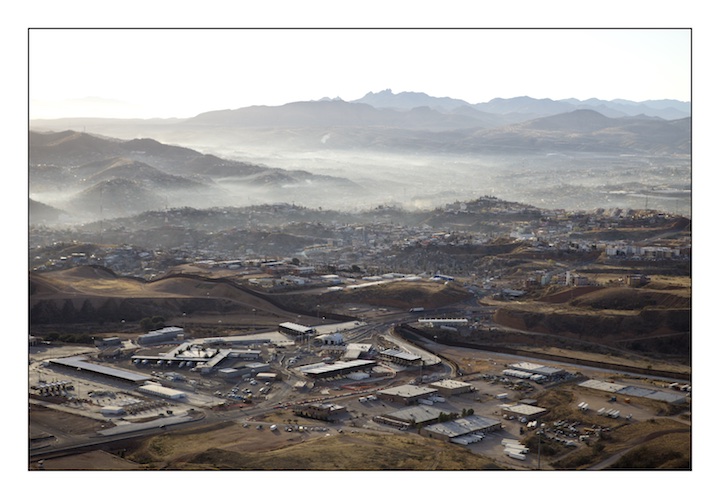

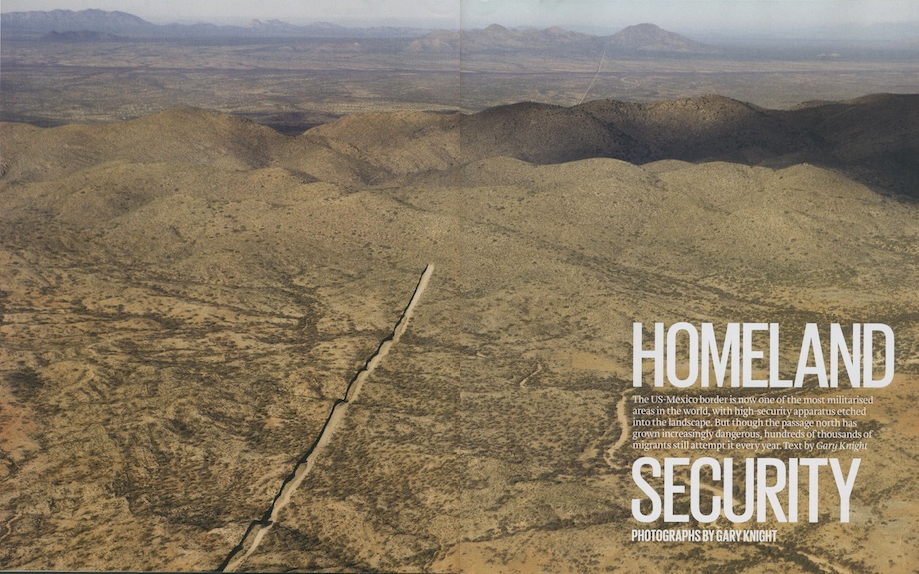

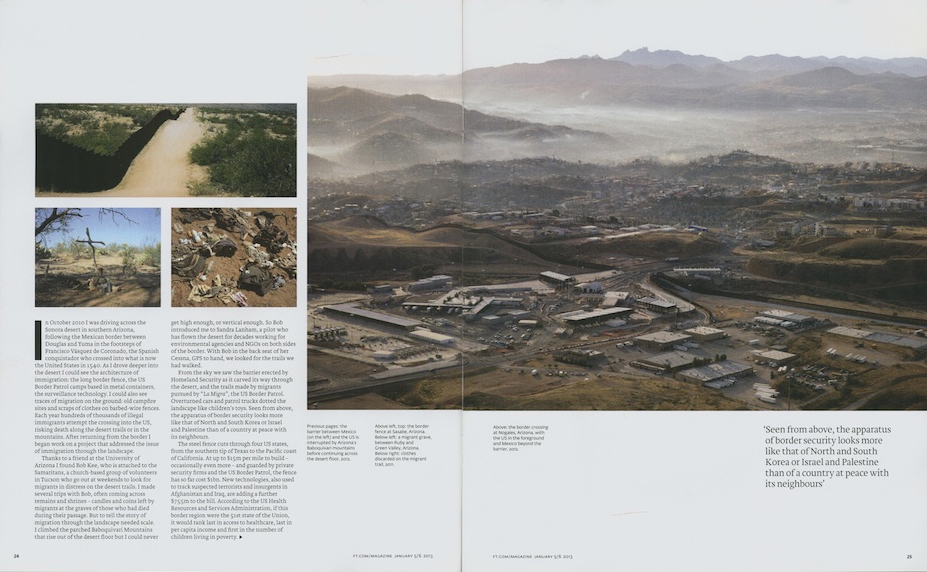

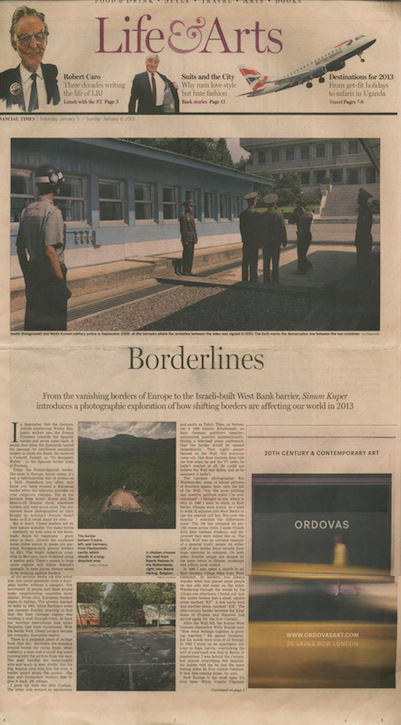

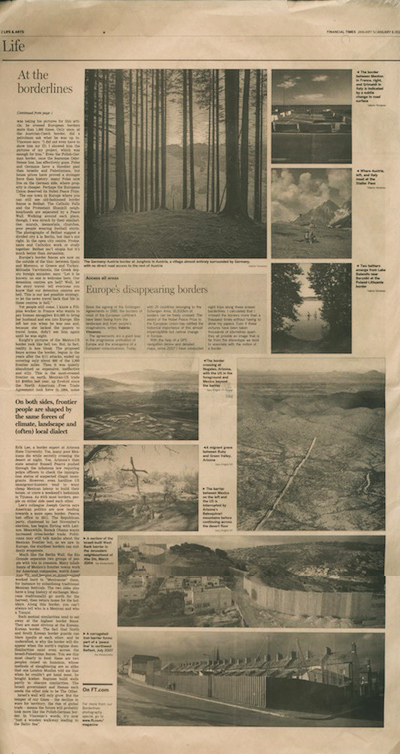

The industrialization and militarization of the border and the integration of technology advanced during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq has changed the US-Mexican border region dramatically during the last decade. It is now one of the most militarized areas in the world. As the apparatus of border security rises out of the Sonoran Desert it resembles more North & South Korea or Israel & Palestine than a country at peace with its neighbors. The construction of the $15 million per mile border fence guarded by private security firms and US Customs & Border Patrol has cost $1 billion dollars so far and new technologies used to track the suspected terrorists and insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq are being deployed to catch the poor, adding to the bill a further $755 million dollars.

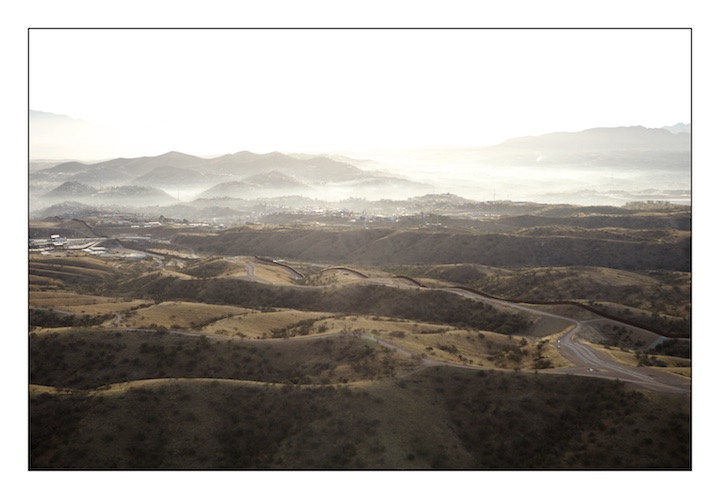

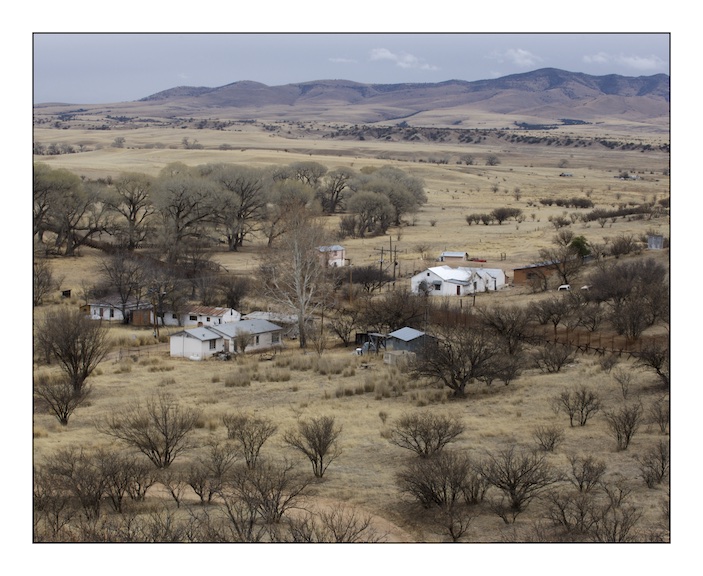

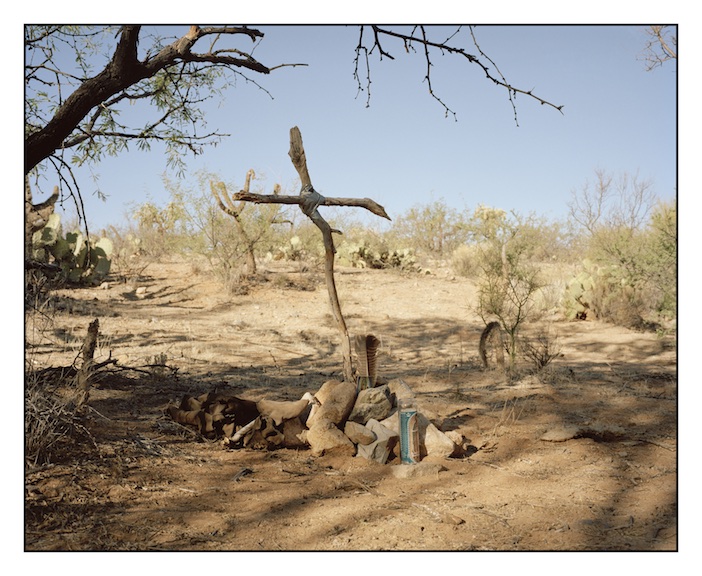

Migrants embark on increasingly desperate attempts to evade the drones or heat seeking technology. Forced to skirt the steel fence and watch towers that stretch for hundreds of miles migrants seeking a better life cross the harshest mountainous desert terrain. They die horrible deaths on remote trails and deer paths, paths that overlook the new desert settlements with names like Desert Bell populated by second generation migrants from Europe. The landscape is an incinerator of dreams, scorching men into the desert sand like dead livestock, it is a place where thousands of women and girls have been raped, the privilege of young men who peddle humans unimpeded by fear of justice.

According to the US Government the actual numbers of migrants crossing the border has decreased but according to NGO’s working locally the number of migrant deaths is increasing as the crossing has become more difficult. We will never know how many people try to cross and succeed, or how many die, in both cases they disappear into the landscape.

The issue of immigration looms large in the political life of America, especially this election year and has become a divisive and contradictory issue for Republicans and Democrats alike. They both seek to appear tough on immigration at a time when they are trying to appeal to Latin voters. With the increase in volume of the political dogma intelligent discourse has been curtailed.

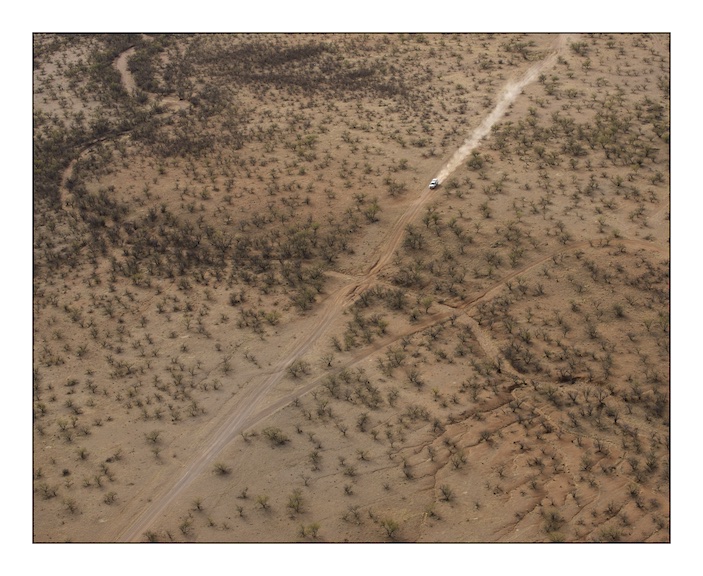

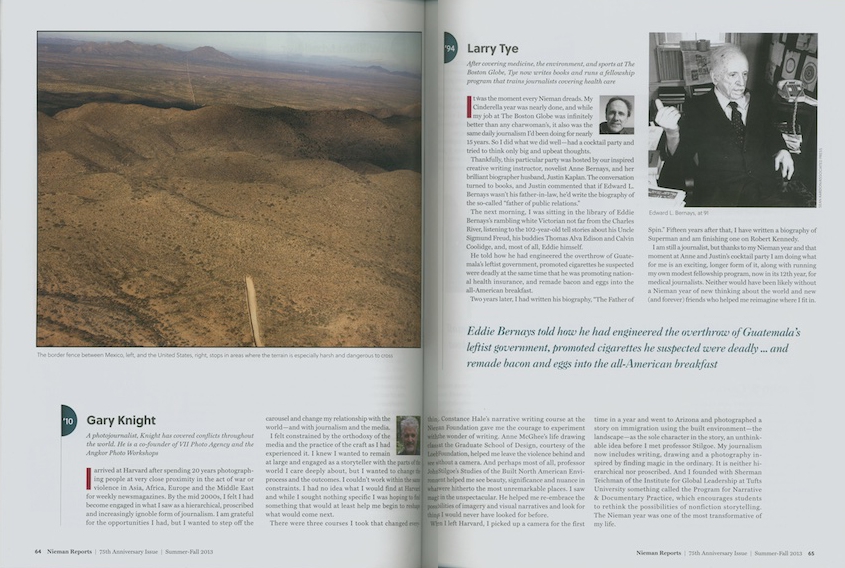

This essay examines the presence of immigration in the environment and landscape of southern Arizona on the Mexican border between Douglas and Yuma. Photographed both from the air and the ground this series shows both the profound impact and scale of the border architecture and technology of immigration on the landscape and the intimate experience of the crossing. From the air we see the barrier Homeland Security has erected as it carves through the landscape toward the Pacific Ocean and the trails made by migrants who walk through the desert pursued by ‘La Migra’. Overturned cars and Border Patrol trucks in pursuit of migrants dot the landscape like toys. It examines on a local scale the impact of the apparatus of border security on the landscape, for example: car tires chained together and dragged behind trucks to ‘cut’ the trail at dusk, tracks in the sand, emergency beacons for migrants in distress who can walk no further, water containers left for migrants by sympathetic NGO’s, discarded clothing and blankets used to cover the tracks left behind in the sand by shoes and shrines to the dead.

Click here for larger gallery view

Publications

+ Reading List

The Devil’s Highway: A True Story. 2005, by Luis Alberto Urrea

Enrique’s Journey. 2007, by Sonia Nazario

Exodus. 2008, by Charles Bowden and Julian Cardona

Inferno. 2006, by Charles Bowden and Michael Berman

The Charles Bowden Reader. 2010, by Charles Bowden

Outside Lies Magic: Regaining History and Awareness in Everyday Places. 2009, by John Stilgoe

Landscape and Images. 2005, by John Stilgoe

Sin and Syntax: How to Craft Wickedly Effective Prose. 2001, by Constance Hale